The book ”Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin” written by Igor Belza was translated from Russian into Croatian and published by the Mala zvona publishing house

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

Red Square, Moscow (photo: © Mirna Rudan Lisak)

By Božo Kovačević

Graduated from the Zagreb Faculty of Philosophy, former Member of Croatian Parliament, Minister in the Government of the Republic of Croatia and Ambassador to Moscow, lecturer at the Dag Hammarskjöld Graduate School, co-founder of “Gordogan”, author of three books and numerous publications, Telegram columnist, Honorary Member of the Croatian Society “Alexandar Scriabin”

Working as the Croatian Ambassador in Moscow, I learned that Scriabin Festival is held there and that there is the Scriabin Museum and Scriabin Fund. I soon came to the information that the co-organizer of the Scriabin Festival is one of the descendants of that famous Russian composer, Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin. I asked the secretary to invite that gentleman to a meeting at the Embassy of the Republic of Croatia. Thus, at the agreed time, a strong gentleman of fifty-something appeared at the Embassy. Striking on him was a short, well-groomed beard, already gray as his hair. At first he was quite reticent in anticipation of finding out why I had called him. I explained to him that I was interested in the development of cultural cooperation between the Republic of Croatia and the Russian Federation. As some of the Croatian musicians have Scriabin’s works in their repertoire, perhaps we could arrange for one of them to be a guest in Russia, which was to be organized by one of the associations that promote Scriabin’s work.

Plate on the entrance to the Memorial Museum of A. N. Scriabin, Moscow

Sasha came to life. He readily provided details of plans and programs and suggested possible forms of cooperation with clearly defined commitments. He would take over the issue of obtaining an invitation, providing a performance hall and a rehearsal piano, as well as printing posters and program leaflets, and the Embassy was to provide financial assistance and accommodation for the contractor. We have very precisely agreed on the deadlines within which each of the planned tasks should be performed. As I knew for sure that Croatian pianist Veljko Glodić also had Scriabin’s works in his repertoire, I suggested that he be the first artist we would invite within the framework of such a collaboration. However, due to certain prejudices about Russians as not very business-oriented people, and due to sporadic experiences that confirmed such prejudices, it seemed unlikely that everything that Sasha and I agreed would be realized as planned. But I was wrong. Sasha proved to be a reliable man, a skilled organizer and manager, and a man of his word.

„Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin and his wife Ana Yuryevna Scriabina are true friends, dear people and recognized experts in the cultural life of Russia. The founding of the Croatian Society “Alexander Scriabin” is largely achieved thanks to their efforts as well.“

Thus began our cooperation, but also our precious friendship that marked not only my ambassadorial mandate in Moscow but also the many years that followed my return. Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin and his wife Ana Yuryevna Scriabina are true friends, dear people and recognized experts in the cultural life of Russia. The founding of the Croatian Society “Alexander Scriabin” is largely achieved thanks to their efforts as well.

You may also like our other publications…

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

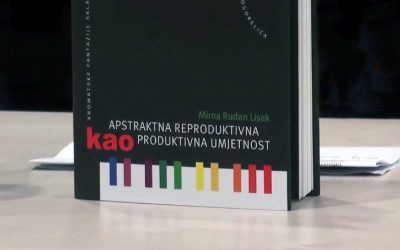

Book entitled “Abstract Reproductive as Productive Art”

First book in Croatia on Scriabin; subtitle: Chromatic fantasies of the composer A. Scriabin, painter A. Jawlensky and pianist I. Pogorelich

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

Prof. Božo Kovačević, former Ambassador of the Republic of Croatia to the Russian Federation, writes about his friendship with Scriabin’s descendant

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

The book ”Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin” written by Igor Belza was translated from Russian into Croatian and published by the Mala zvona publishing house

Book entitled “Abstract Reproductive as Productive Art”

First book in Croatia on Scriabin; subtitle: Chromatic fantasies of the composer A. Scriabin, painter A. Jawlensky and pianist I. Pogorelich

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

Prof. Božo Kovačević, former Ambassador of the Republic of Croatia to the Russian Federation, writes about his friendship with Scriabin’s descendant

Valery Kastelsky and Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 7

R. Dalibaltayan about his Professor V. Kastelsky, one of the greatest pianists and pedagogues of the second half of the 20th century

Recent Comments