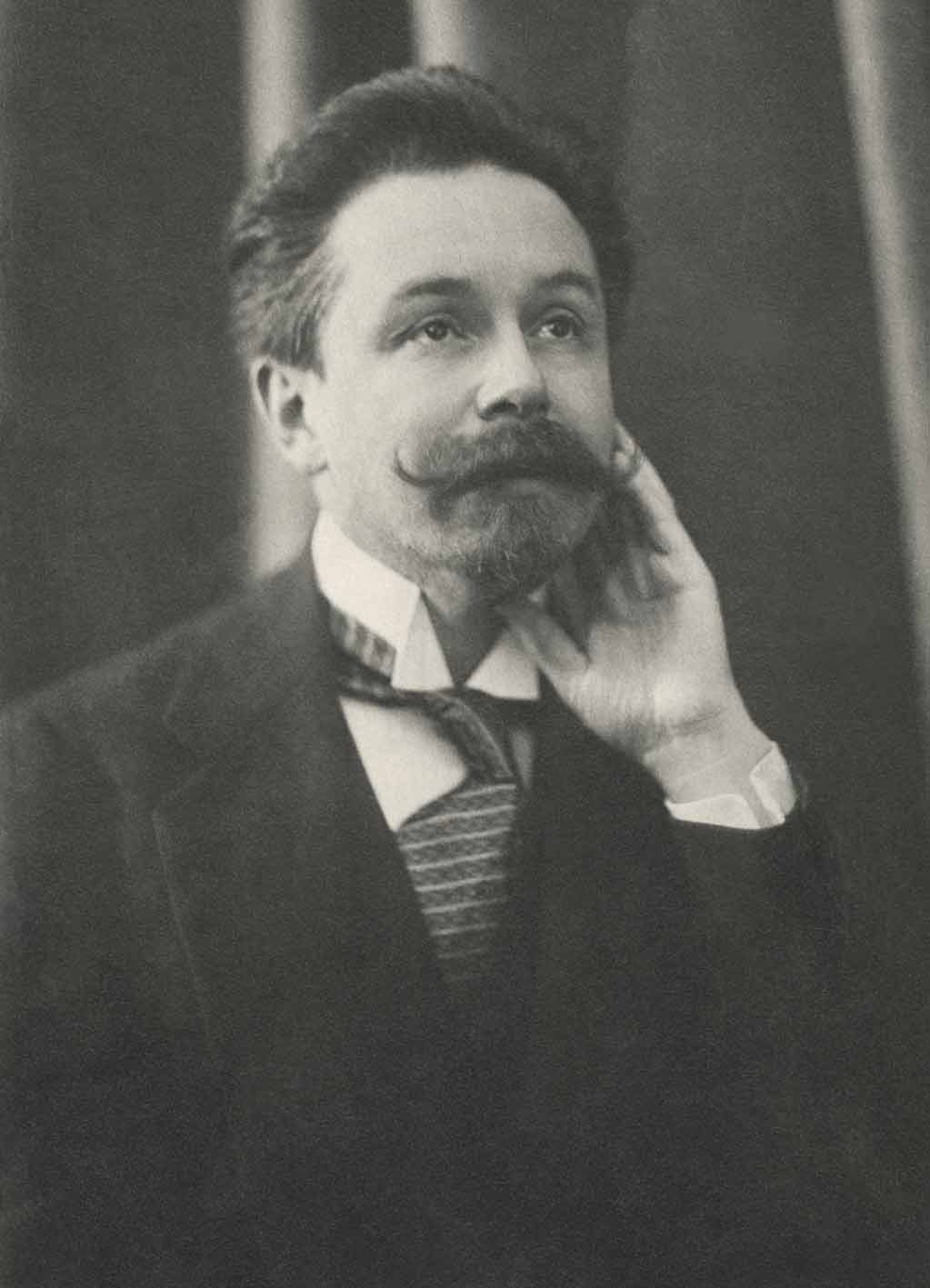

The composer’s portrait taken in 1914 (photo:

© Memorial Museum of A. N. Scriabin, Moscow)

ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH SCRIABIN: SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARTIST

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin [1] (Moscow, 6 January 1872—Moscow, 27 April 1915) is a Russian composer and pianist who initially created a highly lyrical and idiosyncratic tonal language inspired by the music of Frédéric Chopin. Unlike the later Nikolai Roslavets and Arnold Schönberg, Scriabin developed a growing atonal system, which was in accordance with his idea of mysticism, preceding the Schönberg’s twelve-tone technique and other serial music. He can be considered the primary figure of Russian musical symbolism and the proclaimer of serialism.

Scriabin was born at the time when the Russian literary temperament was changing—a period known as the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. It was a movement that encompassed a number of strong artistic personalities of different worldviews (from mysticism and aestheticism to apocalypticism), and many artists of the time were also influenced by Marx’s and Nietzsche’s philosophies, by Helena Blavatsky’s theosophy, and by Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy. Poets and writers such as Alexander Blok, Konstantin Balmont, Boris Pasternak, Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vyacheslav Ivanov appeared, and it was in this spiritual surroundings that Scriabin developed his distinctive views on art and the meaning of human existence.

The family of Alexander Scriabin belonged to the Russian nobility. Scriabin inherited his musical talent from his mother, the pianist Lyubov Petrovna Scriabina (born Schetinina), who died when he was only one year old. After his wife’s death, Scriabin’s father Nikolai Alexandrovich completed his studies in Diplomacy and Oriental languages at the Moscow University, and he accepted a job at the Russian Embassy in Istanbul. He entrusted the upbringing of his son to his grandmothers and sister Lyubov Alexandrovna, who gave Scriabin first music lessons. In his early age, Scriabin also showed an exceptional talent for other branches of art, thus—besides playing the piano and composing—he also wrote poetry and was fascinated by dramatic art.

In 1882, Scriabin started attending private piano lessons with Georgy Eduardovich Konyus, and in the same year he was enlisted in the Second Moscow Cadet Corps. He was an outstanding talent, as later confirmed by Anton Rubinstein—the famous Russian pianist, composer and conductor who founded the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1862. Scriabin’s musical development was in accordance with his romantic role models, and as a pianist he was known for refined interpretations rich in sonic color and dynamic range of nuances. From 1885 to 1888, he attended classes given by the famous Russian pianist and pedagogue Nikolai Zverev, and then at the Moscow Conservatory he began studying the piano with Vassily Safonov and composition with Sergei Taneyev. The study of the composition was later to be continued with Anton Arensky, but due to disagreements with the new professor Scriabin gave up his diploma. Nevertheless, in 1892 he graduated with the Little Gold Medal in piano performance. The same year, the Grand Gold Medal, awarded for composition, was won by Sergei Rachmaninoff.

In 1894, Mitrofan Belyayev, a Russian music publisher, started publishing Scriabin’s works, and from that moment on, the composer’s career was on the rise. Some of his most significant works have found their way to audiences, such as the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra Op. 20, Preludes Op. 11, Second and Third Piano Sonatas, as well as Fantasy Op. 28. He resided several times in Paris, where in 1896 he made his European debut at the Érard Hall. Almost a decade later in Switzerland he wrote his Fifth Piano Sonata Op. 53, rejecting the lyrical expression and gradually transforming himself into a modernist composer emancipated from the strict laws of classical harmony.

From 1898 to 1902, Scriabin was teaching the piano at the Moscow Conservatory. However, in 1903, after Belyayev’s death, Scriabin’s income declined significantly and the situation worsened in 1906, when he stopped working with the Jurgenson and Zimmermann publishing houses. Vladimir Stasov, a Russian music writer and critic, saved him from a financially hopeless situation by including him again in the Belyayev Foundation. And after a meeting with Russian conductor and composer Sergei Koussevitzky, Scriabin joined the board of the publishing house Éditions Russes de Musique, which operated in Germany, Russia, France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

In 1909, with the performance of the Poem of Ecstasy in St. Petersburg, Scriabin’s reputation in Russia reached new heights. During his career he composed almost exclusively piano and orchestral music, and gradually he developed his own distinctive musical language leading to Expressionism. His work is rich in polymetry and polyrhythm, and his original harmonic procedures foreshadowed atonality. It is believed that under the influence of synesthesia Scriabin realized that each musical tonality has the corresponding colour, thus he gradually transmitted his musical language into the chromatic system based on the optics of Isaac Newton.

Being aware of Scriabin’s preoccupation with the relationship of colors, certain syllables of words, tonality and chords, his friend Alexander Mozer constructed an electrical device with colorful lamps, the so-called “tastiera di luce.” It was during this period that Scriabin began composing his most significant orchestral work, Prometheus: The Poem of Fire, in which he abandoned the traditional understanding of tonality to compose numerous synthetic chords, which he most often constructed on intervals of the fourth. One of the most famous such chords is the mystic chord, also known as the Prometheus chord, because the composer used it extensively in his orchestral masterpiece, for the performance of which he composed a visionary section for a light organ that today could be considered the forerunner of the modern light-show.

In 1913, Henry Wood conducted Prometheus in London, after which Scriabin composed his last significant works—Piano Sonatas No. 8, 9 and 10, and the composition Vers la flamme (Towards the flame). It is worth noting that all his compositions are marked with mystical and ecstatic atmospheres, and he advocated the thesis of the cathartic power of music and the idea of a pantheistic synthesis of all the arts. He wanted to achieve all this in his unfinished musical-theatrical work The Mysterium, but death overtook him while making sketches for that grandiose apotheosis of music, dance, colour and spirituality, whose premiere was to be set on the top of the Himalayas in India.

Scriabin’s musical work is huge; he is the author of numerous piano works: sonatas, poems, preludes, etudes, mazurkas, waltzes and nocturnes; and his most important compositions are The Piano Concerto in F sharp minor, Op. 20 (1896–1897); Rêverie for Orchestra, Op. 24 (1898); Symphony No. 1 in E major, Op. 26 (1900); Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 29 (1901); Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 43—The Divine Poem (Le Divin poème, 1902–1904); The Poem of Ecstasy, Op. 54 (Le Poème de l’extase, 1905–1908); Prometheus: The Poem of Fire poem, Op. 60 (Prométhé: Le Poème du feu, 1908–1910) and Mysterium, multimedia interactive stage work (1903-1915, unfinished work).

[1] Source: Rudan Lisak, M. Abstract Reproductive as Productive Art: Chromatic Fantasies of the Composer Alexander Scriabin, Painter Alexej Jawlensky and Pianist Ivo Pogorelich, Matica hrvatska, Sisak, 2015; Glodić, V. Alexander Scriabin and Contemporaries from Central Europe: Béla Bartók and Dora Pejačević in: Fortepiano, Moscow, 2015; Hull, A. E. A Great Russian Tone-Poet Scriabin, Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, New York, 1918 (Entire Scriabin’s biography available at pp. 5-81); Bowers, F. Scriabin: a Biography of the Russian Composer, 1871–1915, Tokyo and Palo Alto, CA, 1969; Croatian Encyclopedia—the electronic display and search release, Portal Leksikografskog zavoda Miroslav Krleža, Zagreb, visited 1 May 2015; to learn more see: Wikipedia