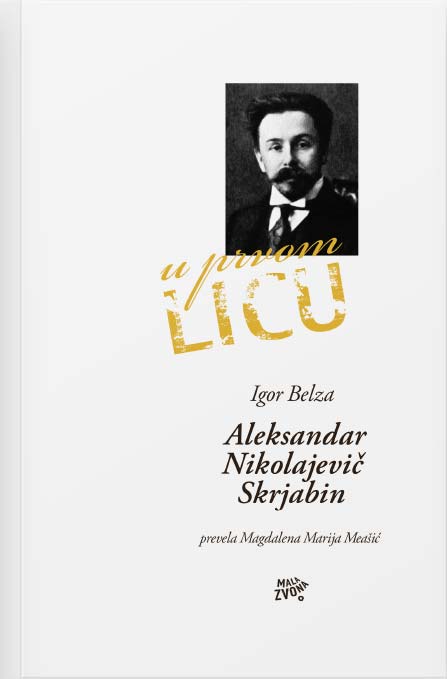

The book ”Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin” written by Igor Belza was translated from Russian into Croatian and published by the Mala zvona publishing house

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

Alexander Scriabin playing the piano (photo: © Memorial Museum of A. N. Scriabin, Moscow)

By Prof. Veljko Glodić Ph.D.

The translation of the book was initiated by the Croatian Society ”Alexander Scriabin”

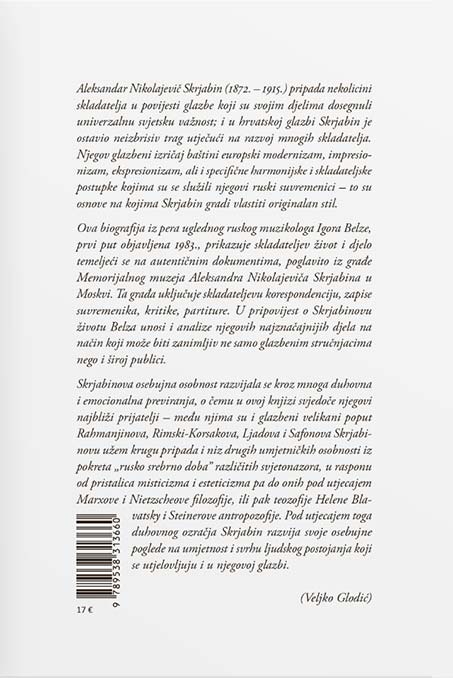

Aleksandar Nikolayevich Scriabin (1872 – 1915) belongs among the few composers in the history of music whose works achieved universal world importance. Scriabin also left an indelible mark on Croatian music, influencing the development of many composers. His musical expression inherits European modernism, impressionism, expressionism, but also specific harmonic and compositional procedures used by his Russian contemporaries―these are the foundations on which Scriabin builds his own original style. This biography written by the distinguished Russian musicologist Igor Belza, first published in 1983, presents the composer’s life and work based on authentic documents, mainly from the materials of the Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin Memorial Museum in Moscow. This material includes the composer’s correspondence, notes by contemporaries, reviews, and scores. In the narrative of Scriabin’s life, Belza includes analysis of his most significant works in a way that can be interesting not only to music experts but also to a wider audience. Scriabin’s distinctive personality developed through many spiritual and emotional turmoils, as evidenced in this book by his closest friends―among them are musical giants such as Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, and Safonov. Scriabin’s close circle also includes a number of other artistic personalities from the ”Russian Silver Age” of different worldviews, ranging from supporters of mysticism and aestheticism to those influenced by the philosophy of Marx and Nietzsche, or the theosophy of Helena Blavatsky and Steiner’s anthroposophy. Under the influence of this spiritual atmosphere, Scriabin developed his distinctive views on art and the purpose of human existence, which are also embodied in his music.

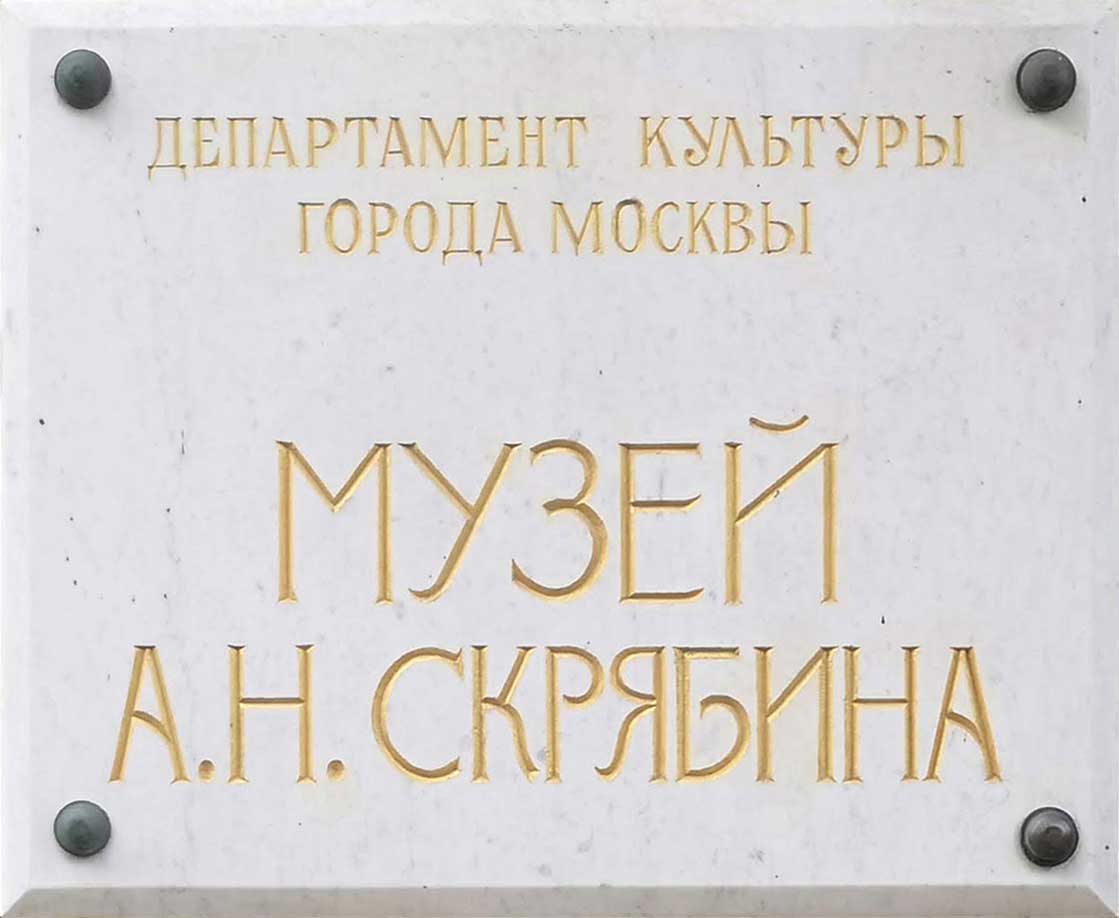

This biography written by the distinguished Russian musicologist Igor Belza, first published in 1983, presents the composer's life and work based on authentic documents, mainly from the materials of the Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin Memorial Museum in Moscow

Publishing house Mala Zvona

The book, translated by Magdalena Marija Meašić, was published by the publishing house Mala zvona (Zagreb, 2023). It was presented on November 24, 2023, in the Vaclav Huml Concert Hall at the Academy of Music in Zagreb. Prof. Ruben Dalibaltayan and editor Sanja Lovrenčić talked about the book, while selected Scriabin’s piano preludes were performed by Stipe Prskalo, Jan Niković, and Severin Filipović.

The book is the result of cooperation with the Scriabin Museum

The book is the result of cooperation with the Scriabin Museum

Publishing house Mala Zvona

The book, translated by Magdalena Marija Meašić, was published by the publishing house Mala zvona (Zagreb, 2023). It was presented on November 24, 2023, in the Vaclav Huml Concert Hall at the Academy of Music in Zagreb. Prof. Ruben Dalibaltayan and editor Sanja Lovrenčić talked about the book, while selected Scriabin’s piano preludes were performed by Stipe Prskalo, Jan Niković, and Severin Filipović.

Možda će Vas također zanimati…

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

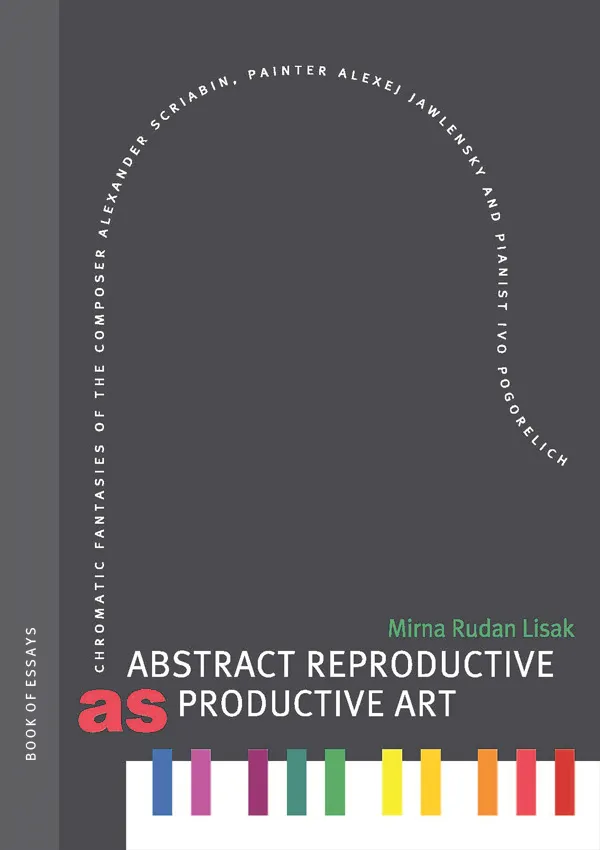

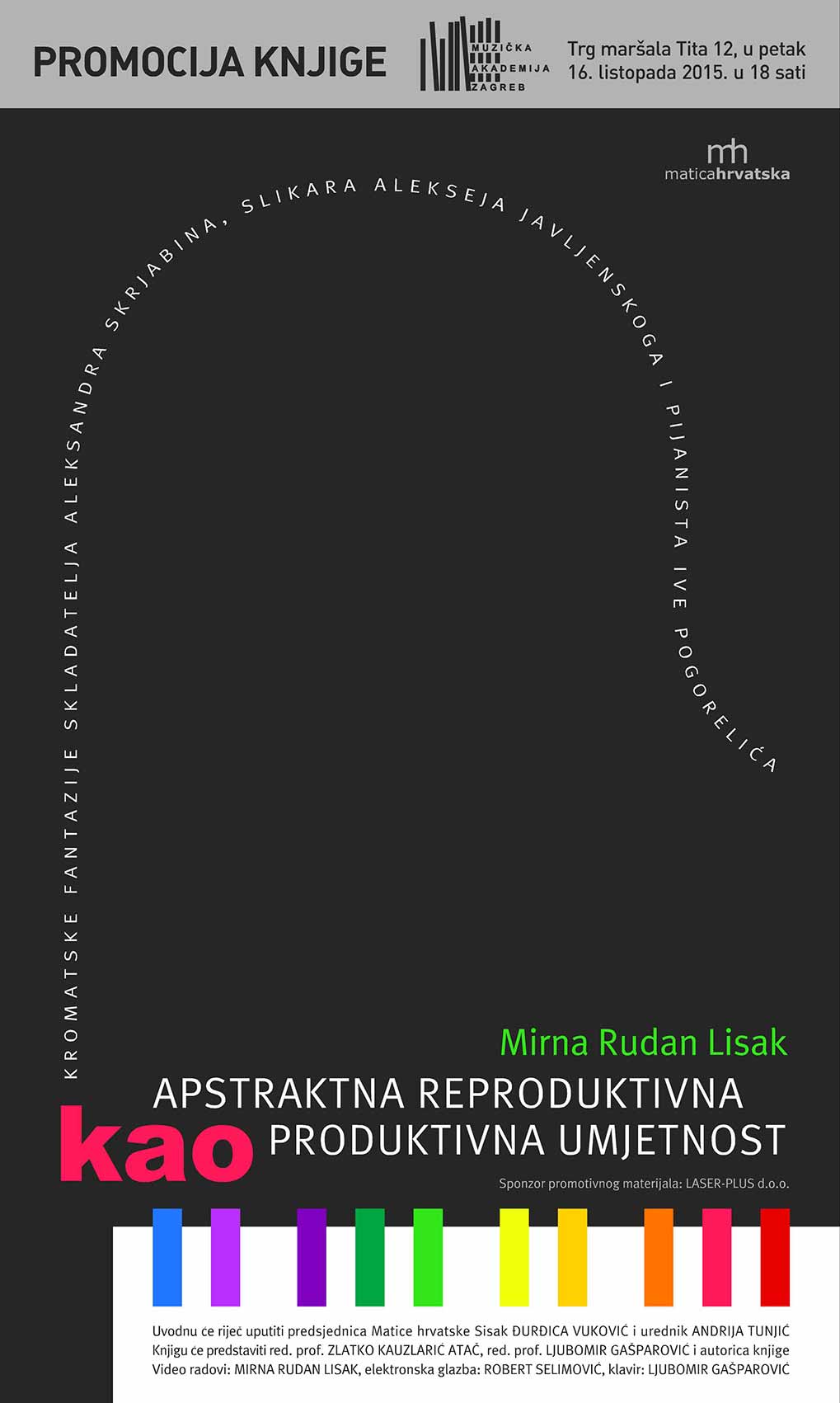

Book entitled “Abstract Reproductive as Productive Art”

First book in Croatia on Scriabin; subtitle: Chromatic fantasies of the composer A. Scriabin, painter A. Jawlensky and pianist I. Pogorelich

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

Prof. Božo Kovačević, former Ambassador of the Republic of Croatia to the Russian Federation, writes about his friendship with Scriabin’s descendant

Translation of Igor Belza’s book on Scriabin

The book ”Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin” written by Igor Belza was translated from Russian into Croatian and published by the Mala zvona publishing house

Book entitled “Abstract Reproductive as Productive Art”

First book in Croatia on Scriabin; subtitle: Chromatic fantasies of the composer A. Scriabin, painter A. Jawlensky and pianist I. Pogorelich

How I met Alexander Serafimovich Scriabin

Prof. Božo Kovačević, former Ambassador of the Republic of Croatia to the Russian Federation, writes about his friendship with Scriabin’s descendant

Valery Kastelsky and Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 7

R. Dalibaltayan about his Professor V. Kastelsky, one of the greatest pianists and pedagogues of the second half of the 20th century

Recent Comments